When last week’s Brexit-related “What is the EU?” Google story hijacked our collective social feeds with the strident persistence of a carnival barker, it sounded too good to be true, what with the story playing so nicely into the global narrative of xenophobic working class louts rising up, and all.

I made a mental note to check the numbers out before sharing on my own feed because, as a social media slash digital-type worker bee, I know how hard it is to draw sound conclusions from social media and search behavior (remember the epic misreporting of Google searches and flu trends?)

This is particularly worrisome when the conclusions you draw feed into a social conversation already rife with misinterpretations of facts, and willful mischaracterizations of large groups of people. Specifically, please refer to my tongue-in-cheek characterization of Trump and Brexit “leave” supporters above.

Those who report on and interpret data wield a lot of power these days. Specifically, the emotional power to reinforce biases in a time when tensions and incivility are very efficient breeding grounds for the quick acceptance of stereotypes based on personal bias, repetition, and little time or inclination for independent verification of facts.

So, after the referendum on whether or not to leave the UK, the GoogleTrends team reported a “+250% spike in ‘what happens if we leave the EU” in the past hour'” via Twitter.

That tweet is interesting for three reasons:

1. The Brexit GoogleTrends tweet plays on the immediacy of the situation and our emotions.

Telling us “in the last hour” heightens the immediacy of the news. “Spike” infers high numbers more than percentage increase, doesn’t it? This immediacy heightens our emotions and encourages us to skip past the obvious (see below) and focus on the what the author is telling us right now. We put our skepticism and critical thinking on hold in exchange for the savoury headline.

2. This play on emotions makes it easier for casual readers to mistakenly infer percentage increase with a high quantity.

This happens ALL THE TIME. As you know, a 250 percent spike is only relevant when you understand what the base quantity is. As in, were there 100 searches before and now there are 350? That’s a 250 percentage increase, but hardly one worth noting compared to the 52 percent of voters who voted to leave (out of the more than 30 million who voted in the Brexit referendum).

So. How many people are we talking about with this 250 percent increase? One blog reports 1,000. Yep. 1,000.

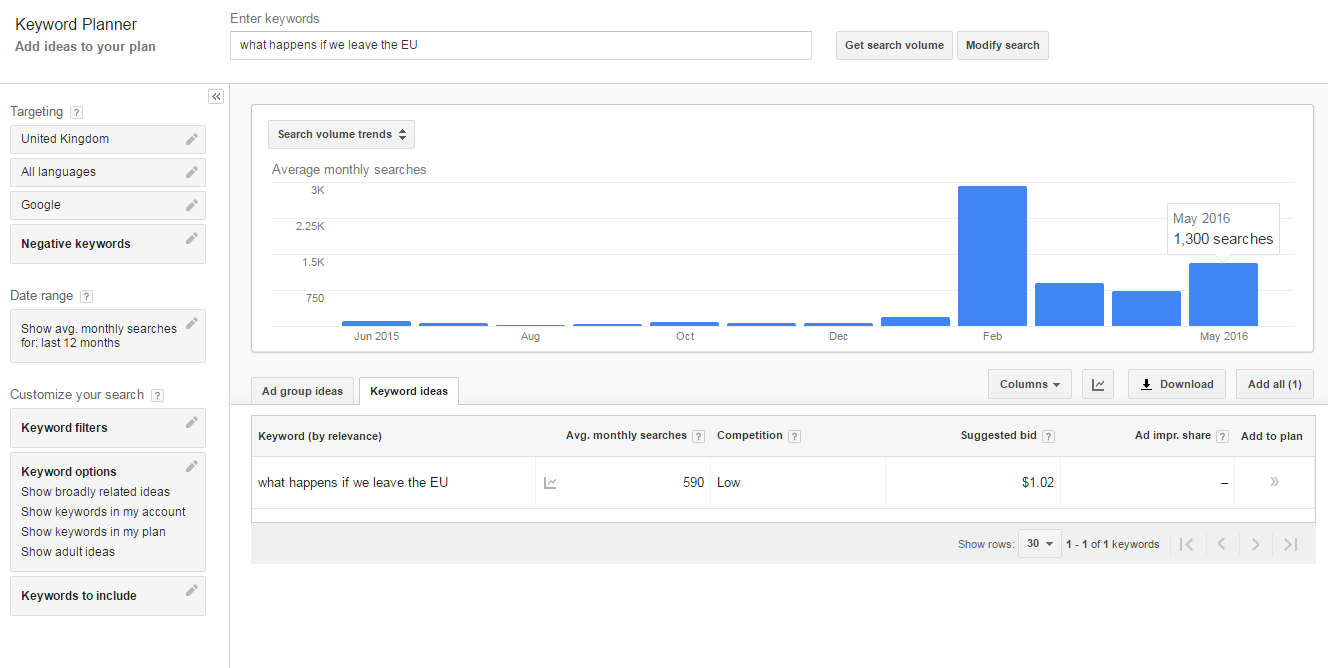

As several bloggers have pointed out by now, GoogleTrends just measures the relative increase/decrease of search terms over time, but not the amount. Steve Patterson instead searched on Google AdWords, which does actually count. Using that, you get closer to slightly less than a thousand, according to his calculations, and that of Remy Smith.

Patterson takes the Washington Post to task for misreporting the actual search term, which lowers the numbers even more (see his graphic, below and the original post here):

3. We are mistakenly inferring that those who voted to leave the EU are those who searched “what happens if we leave the EU?”

How do we even know that the people who searched the consequences of leaving are the same people that voted to leave? Isn’t it quite as reasonable to say that those in favor of staying are now searching to find out what will happen next? Or a mix?

Too quick to report, too slow to question: Worry about the real trend instead

So, another disappointing reminder that the emotional nature of social media reporting of “facts” fuels our propensity to believe, to share, and to move on without fulling understanding what we’re propagating. And this is the real trend that I’m worried about, because it shapes public attitudes and opinions and threatens our ability to see and understand information based on facts versus what we’d like to believe. Given the uncivil nature of public discourse these days, that’s a dangerous proposition.