This is a picture of my son’s ball of yarn. A bad listicle is like a knotted ball of yarn… sometimes there’s a lot of untangling to do to get to the facts.

I remember the day a managing editor uttered the word “listicle.” I giggled and was torn between a Beavis and Butthead snort and a disgusted of-course-only-a-guy-would-say-that reaction.

Shortly thereafter, I designed my first one (the effects of the recession on Wisconsin, if you’re curious). It was actually a charticle because it had pictures (The American Journalism Review doesn’t like charticles. I suspect they like listicles even less.)

Wired recently wrote in defense of listicles. It is reassuring to find out that listicles won’t, in fact, give you ADHD. The Guardian is more tongue-in-cheek skeptical, but kindly proffers a few literary examples to redeem the form. I think they lay it on a little thick in number 7 but it’s a good read. More seriously, the trend spawned a new genre, the apocalypsticle, roundly lambasted by Politico a few months ago as “dumbing up” the tragedy of Ukraine.

I won’t go into our obsession with lists. People like them, and you already know why they do. I confess that I’ve never been successful at writing a listicle. I’m too wordy. I rebel at the constraints of a finite number. I just can’t get the thing to hang together to my satisfaction. I need paragraphs to do that. So perhaps I’m just a little jealous.

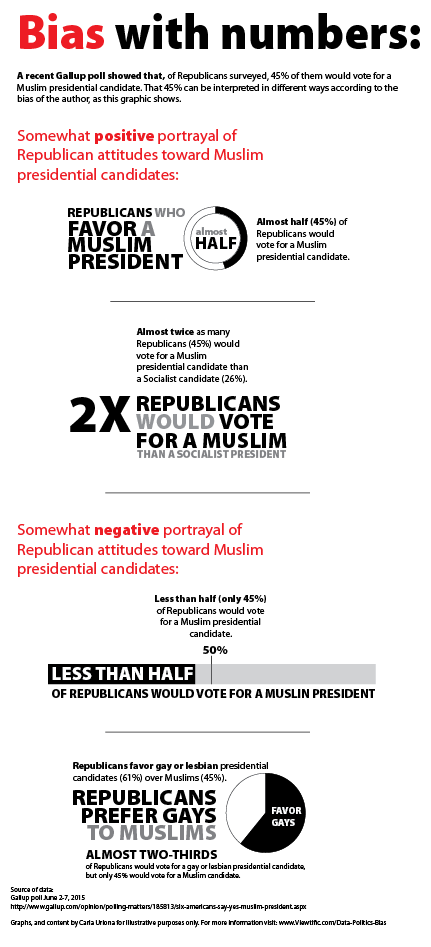

But I am concerned that our collective obsession and fascination with the genre is not making us stupider, per se, but that—coupled with our penchant for so-called data nuggets—it is becoming too acceptable for journalists and others to conjure up a type of content that does not always responsibly use data and facts to support a story.

Listicles: If you’re going to compare apples to bicycles, go ahead. But don’t pretend you’re just comparing apples.

My biggest beef with the quick comparisons use in listicles is that they make it too easy to cherry-pick disparate data points and thread them together into a seemingly logical order to support a seemingly logical claim. They don’t always use logical comparisons. You’ll frequently see different periods in time compared against each other, or slightly different variables compared as well. If you don’t look closely, you can get the wrong message. And if you do look closely, you’ll be confused. It’s okay to compare things from different time periods, but you need to explain that. You also need to explain which things change from one comparison point to another.

The order in which points are presented in a list can also hide unfeasible comparisons.

If I tell you that, in 2010, 1 million green widgets were produced in the U.S., compared to 5 million red ones produced in 2012, you might think this is a ridiculous comparison and you’d be hard-pressed to understand what, if any, trend existed here. The time period is different, as is the variable.

But what if I separate those comparisons with other items in a list? You might lose track.

1. In 2010, 1 million green widgets were produced in the U.S.

2. In 2014, China is the largest manufacturer of widgets, with the U.S. ranked at number 5.

3. Over the past 5 years In the U.S., the majority of widgets have been produced in the South.

4. Nationally, widget manufacturing plants are closing down.

5. In 2012, there were only 5 million red widgets produced in the U.S.

Now think back to how often you have come across this in a list.

Lists should offer data in order to provide perspective and context

Too many lists and listicles are simply a series of disparate data points that offer the reader no meaningful way to compare numbers with broader context.

If I tell you that there are “x” number of people living in dire poverty in the United States, I owe you a bit more than that.

I need to tell you what percentage that number is out of the broader population, and I need to define that population. I need to tell you what “dire” means. Better, I should give you a dollar amount of poverty (and cite that definition to a credible source) so that you’ll understand the context. I should probably give you the time period for this data. And in a second bullet, it would be helpful if I further provided information about change in this figure over time–preferably a long period of time to discount variances over shorter amounts of time. Here’s a better way to accomplish the first bullet:

Of the [#] million adults* living in the U.S. in 2013, [#] of them (x %) are living at or below 50% of the federal poverty level (an annual income of $5,835 for one person**)

*Adults aged 18-and older

**Federal poverty levels 2014

Citation for data source

The examples above are just that, examples. But the other day I stumbled across Mother Jones’ “10 Poverty Myths, Busted,” It proves my point. I took the time to deconstruct it below.

Not every set of facts lends itself to a list, or a conclusion.

Before you read further, please understand that my notes below are not to undermine the claim of the author, but rather to strengthen it. The notes are not intended to be exhaustive. Reasonable minds can poke holes in them at will. But my point remains the same: We have lists. We have data. We have people very willing to read them and share them. If we have strong facts that actually relate to one another, and we lay those facts out clearly and in a logical order, the reader will draw logical conclusions. But if we don’t do these things, at best, we lead readers down a rabbit hole that leaves them frustrated and confused.

At worst, we turn facts into opinions that are interpreted as facts.

The main problem with this list is the disparate, unconnected (by time, logic, data set) nature of 10 claims that, together, attempt to combat poverty stereotypes. The Mother Jones listicle and its bullets are in bold followed by italics. The text prefaced by “issue” is mine.

1. Single moms are the problem. Only 9 percent of low-income, urban moms have been single throughout their child’s first five years. Thirty-five percent were married to, or in a relationship with, the child’s father for that entire time.*

Issue: To me, this bullet appears to cherry-pick the data. What makes the first 5 years a magic number? What about the first 10, 15 or 18? If there is importance to those first 5 years, context would be helpful.

Issue: It is unclear whether the dads in the relationships are actually living in the household. This matters because whether or not a dad lives in a household affects the income level of the mom and child. If he lives in the household for example, the household income can be higher (if he has an income to contribute), which can affect a mom’s low-income status.

2. Absent dads are the problem. Sixty percent of low-income dads see at least one of their children daily. Another 16 percent see their children weekly.*

Issue: There is a difference between low-income and poverty. The label “low-income” is subjective. The label “poverty” is qualitative (there is a federal poverty level). So if you use a subjective level like “low-income” and don’t define it upfront, you can give the appearance of anything you like, really.

Also note how this bullet is worded. On the flip side, you could also say that a quarter of kids don’t see their dad as often as once a week.

And notice how bullet #1 discusses dads living in the household (presumably), whereas this item discusses dads who live outside of the household.

3. Black dads are the problem. Among men who don’t live with their children, black fathers are more likely than white or Hispanic dads to have a daily presence in their kids’ lives.

Problem: Cherry-picking again. Why single out black dads in this one bullet? There are Hispanic dads who live at or below the poverty level. Ditto white dads. Did MJ simply pick the most appealing (higher) number to make the point stronger?

4. Poor people are lazy. In 2004, there was at least one adult with a job in 60 percent of families on food stamps that had both kids and a nondisabled, working-age adult.

Issue: The time period shifts for these comparisons, making it impossible to compare or understand trends. This bullet dates to 2004. Others (bullets 5 and 6, for example) date to 2012.

5. If you’re not officially poor, you’re doing okay. The federal poverty line for a family of two parents and two children in 2012 was $23,283. Basic needs cost at least twice that in 615 of America’s cities and regions.

Issue: The Economic Policy Institute calculator and date from which this bullet is derived is for 2013. The federal poverty level cited is for 2012. Not a huge deal, but you can expect the numbers to change in a year due to inflation, cost of living, etc.

6. Go to college, get out of poverty. In 2012, about 1.1 million people who made less than $25,000 a year, worked full time, and were heads of household had a bachelor’s degree.**

Issue: Context would be helpful here. 1.1 million people out of how many? And isn’t it expected for new college grads to not make much money? How long have these 1.1 million people cited been in the workforce? Poverty is unacceptable at any level (my opinion here), but telling me that a forty-year-old mother of two with a degree who has been in the workforce for 20 years and is living at the federal poverty level is one thing. Tell me the same thing for a recent grad out of school for a year will send me a different message.

7. We’re winning the war on poverty. The number of households with children living on less than $2 a day per person has grown 160 percent since 1996, to 1.65 million families in 2011.

Issue: This myth is so subjective and vague that it’s hard to dissect. It would be helpful to know if the $2 a day includes or does not include federal assistance (TANF, SNAP, etc.).

8. The days of old ladies eating cat food are over. The share of elderly single women living in extreme poverty jumped 31 percent from 2011 to 2012.

Issue: Clearly, this lacks context to be clear and helpful. What does extreme poverty mean? If you dig into the source report for this, you’ll see on page 3 that extreme poverty is defined as income at or below the federal poverty level. The statistic itself is startling and would be strengthened by an upfront definition of the spectrum of poverty, preferably in dollar figures as well.

9. The homeless are drunk street people. One in 45 kids in the United States experiences homelessness each year. In New York City alone, 22,000 children are homeless.

Issue: To put this into perspective, What is the percentage of homeless kids compared to the percentage of homeless adults with (presumably) addiction problems? The connection between homeless individuals with substance abuse issues and children may be one that is widely discussed, but in terms of statistical comparison here, the pairing is clunky.

10. Handouts are bankrupting us.In 2012, total welfare funding was 0.47 percent of the federal budget.

Issue: It’s difficult to follow the citation, partly due to how you define “2012” and “federal budget.” If you follow the citation, you’ll see that this bullet cites the budget that the president proposed for FY2013 on February 13, 2012 ($3.8 trillion). The key word is “proposed,” and the fact that the budget itself was for FY2013. This was not the 2012 budget, as the wording in this bullet implies. Further, the FY2013 budget itself is hard to pin down. The bullet implies that spending happened as a proportion of an actual budget. But in reality, it’s citing a 2012 figure ($16.6 billion) as a percentage of a proposed budget for a different year (2013), not the actual budget for 2012. Furthermore, remember that the proposed budget is simply a draft, if you will. It must be approved by Congress (remember all the subsequent political wrangling, counter-proposals by Republicans, sequestration, etc. (If you want to know what happened to the 2013 budget however, you can check out CBO’s later analysis.) So saying that total welfare funding in 2012 “was” a percent of a **proposed** budget that was intended for FY2013 is neither correct, nor easy to follow.

Issue: Then there’s how “welfare” is used in the bullet. It’s unclear what that means. Clarifying it upfront would have been more helpful. Presumably the word “welfare” is the $16.5 billion cited by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities for what is known as TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families – financial aid for some poor families). But you have to do a little digging in the source to ascertain that. And using the word “welfare” could mean TANF, and it could mean SNAP (food stamps) as well. Or something else, as this helpful post on Real Clear Politics points out. This is needlessly unclear, given that the term “welfare” is such a politically charged word.

Sources as cited in the above Mother Jones list:

*Source: Analysis by Dr. Laura Tach at Cornell University.

**Source: Census

So, listicles. Use them wisely and well. And if not, stick to the goofy stuff, not the serious stuff. Like, top 6 reasons this post would have been shorter and more effective if I had used a list.